People I have Shot – And Who Have Shot at Me!

Members of the Protestant Orange Order Parade in Belfast

On assignment with ‘sixties photo-journalist David Lewis-Hodgson

Assignment 1 – ‘The Troubles’

The men in the balaclavas were polite but insistent.

“We’d like a little chat,” said their leader amiably as he patted my chest with a pickaxe handle. A canvas hood was pulled over my head and I was led out of the dingy Belfast alley.

The date was September 29th, 1969. A few weeks earlier after an attempted march, by the Protestant Apprentice Boys, through the Catholic Bogside area of Derry had led to days of rioting.

On August 14 the British government, under Harold Wilson, had sent in troops what the government claimed would be an ‘limited operation.

What were to be called ‘the Troubles’ had begun.

Covering the Troubles

In early September, I had been sent to Belfast by a French magazine to photograph the effects of increasing violence on families living both sides of the sectarian divide.

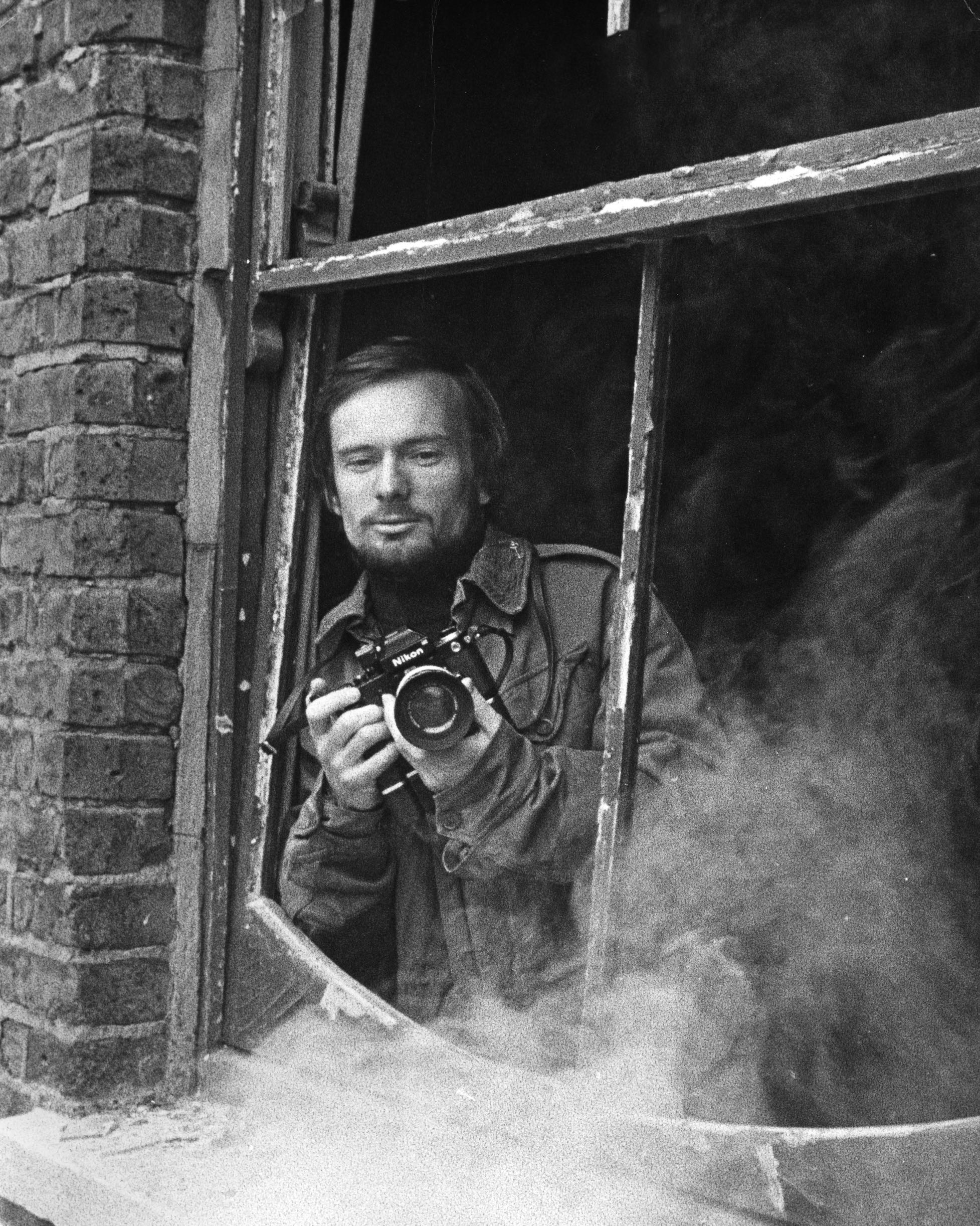

With me I took my two trusted motorised Nikons, with a variety of lens, and my Leica M4. I especially liked this small, discrete, camera with its with a f1.4 lens and silent shutter for occasions when I did not want to be too noticeable.

Covering a riot in Belfast 1972 with one of my Nikons

For the Nikon, I also carried a follow focus telephoto lens called a Novoflex. With its pistol like focus grip and chest support, this looked, rather too alarmingly at times, like a grenade launcher! Especially when poked around the corner of a building in the middle of a riot.

A Novoflex 300mm lens. You focus by squeezing the handle.

After a number of narrow escapes, during which I was mistaken for a member of the IRAor UVF by the British Army and for a British soldier by the IRA and UVF, I painted the black metal end of the lens a bright, canary, yellow just to avoid getting shot at in the future.

Photographing Families

Fortunately, my assignments seldom took me into the line of fire, as my editors were mainly interested in stories about the way in which the conflict was affecting the lives of ordinary people in the Falls Road (Catholic) and Shankill (Protestant) areas.

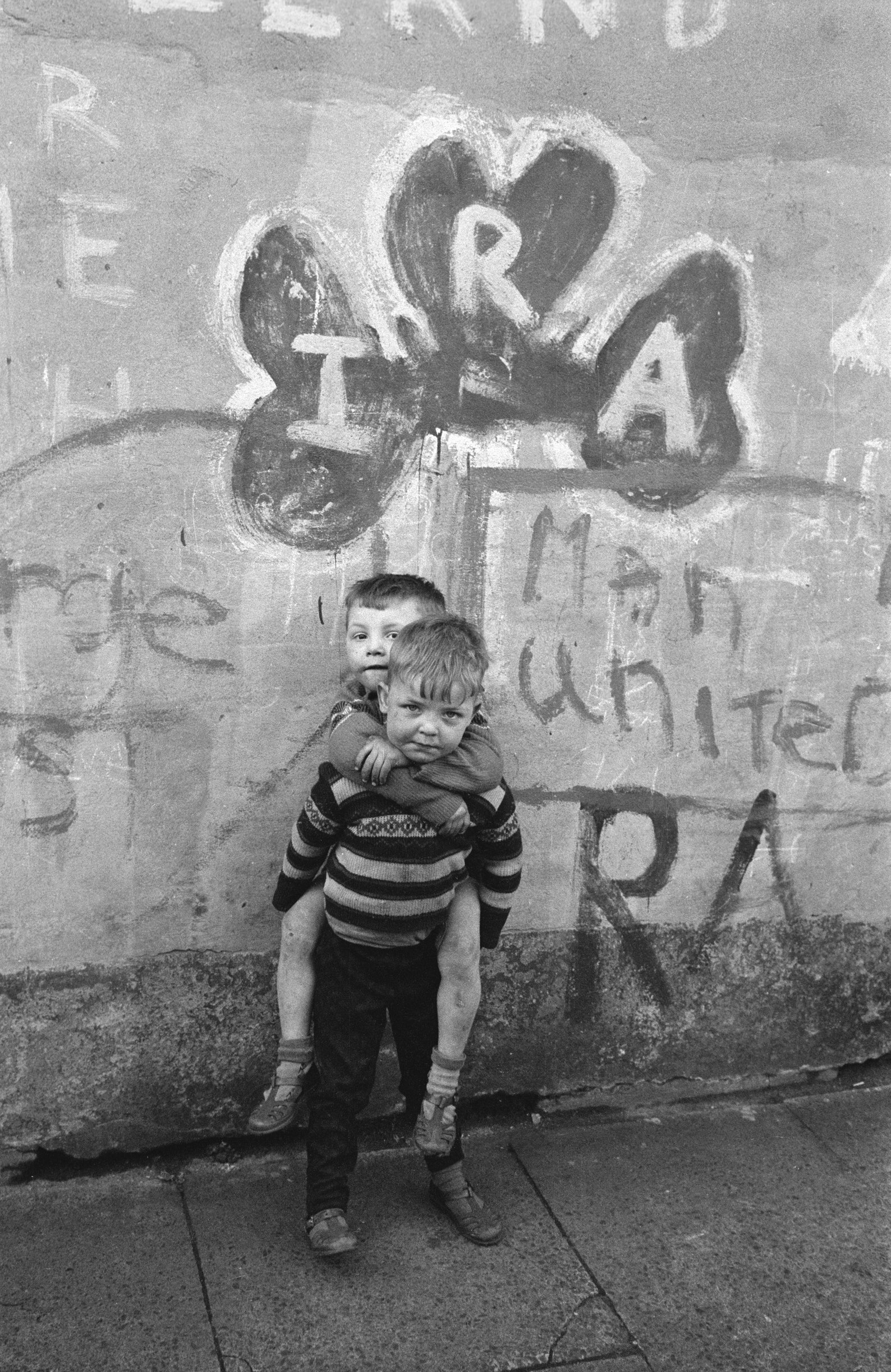

Many families, especially in the Catholic areas, lived in squalid slums

Two little boys pose beneath an IRA slogan

In the early days, I was able to wander freely through the narrow streets around both Catholic area and Protestant neighbourhoods. I photographed the children as they played in virtually traffic free roads and their parents as they struggled to cope with threats and impact of the ever more bitter dispute between previously friendly neighbours.

But on that drab morning in late September my moment of reckoning seemed to have arrived.

Abducted

The leader of the IRA unit which had abducted me demanded to know “what the ‘f***k’ I was doing there. I explained, as calmly as I could, that I was a French born photojournalist working on a magazine feature.

Judging from their response this failed to impress. I feared that, at best, I was in for a beating and probably the destruction by cameras. The worst I preferred not to think about.

I was manhandled through the streets until, ten minutes later, I felt myself pushed roughly into an upright wooden chair.

The hood was pulled from my head. I was in a small, cheaply furnished, bedroom. Pallid afternoon sunlight filtered in faintly through grimy lace curtain,

Things seem to be on the point of turning really nasty.

Then, I remembered the name of a local doctor I had met and spoken to at length about my reasons for being there.

The GP Who Saved My Life

His name was Dr Jim Ryan and, although a Catholic, he had for decades made it his mission help the poor and sick irrespective of their religion.

Jim Ryan greets one of his devoted Protestant patients

He had also been a member of the IRA during the 20s and spent years in British prisons as a result.

The Boys of the Old Brigade. Former IRA men at a reunion. Jim Ryan is extreme right on the back row.

Dr Jim proved to be my ‘get out of jail’ card. Once they had spoken to him the atmosphere changed entirely.

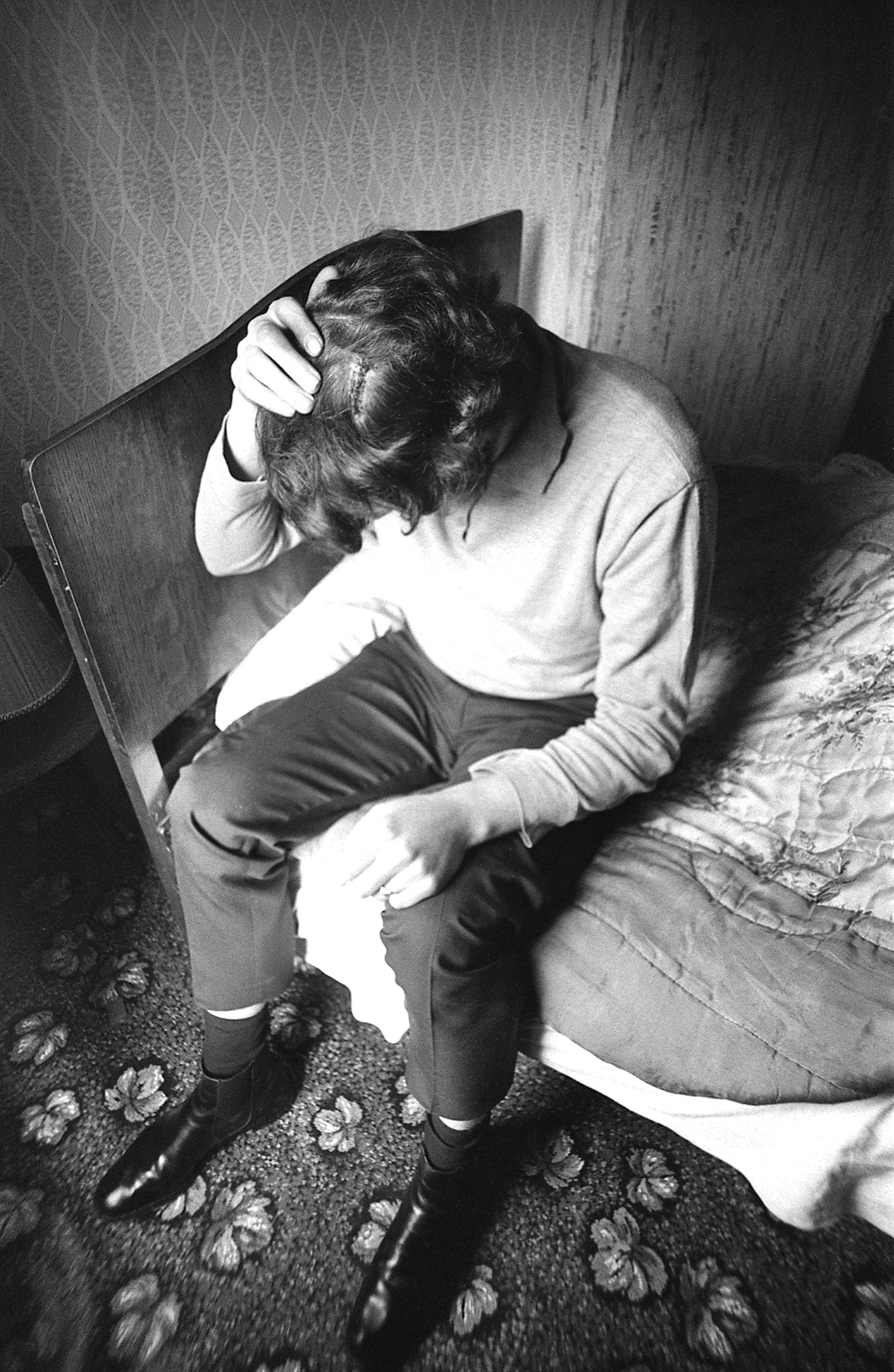

The men remove their balaclavas and the leader turned out to be a friendly 17- year-old who proudly showed me, and allowed me to photograph, the stitches in his head with an injury he said had been caused by the baton of one of the hated B Specials police officers.

A Catholic teenager displays head wound caused, he claimed, by a B Special officer

This incident proves to be the first, but by no means the last, of my encounters with people violently opposed to the work of photojournalists during the years I spent covering assignments around the world.

In my next blog I will describe the hazards of taking covert pictures in a Turkish prison.