Assignment – Behind Bars in a Turkish Prison

Most people are sent to jail after being arrested.

I was arrested while behind bars!

It happened in Turkey and it happened like this.

In 1970, 14-year-old Timothy Davey was enjoying every teenager’s dream adventure. He was travelling the world, with his mother, Jo, and five brothers and sisters, in an old truck, nicknamed Bertha. From England they had made their way down to India spent some time there and then came back via Afghanistan and Turkey.

In Istanbul they met a young, long-haired and bearded American hitchhiker named Steve. He told Tim he had some hashish and asked his new found friend to go with him to meet the buyer.

Knowing such a deal was strictly illegal and punishable by a heavy prison sentence, Tim hesitated. Finally, very much against his better judgement, he was persuaded and drove with Steve to the meet the supposed buyer. On the way they were arrested. Steve, it turned out, had deliberately set him and was, he later learned, an undercover US drugs officer.

Tim Goes to Prison

After a brief trial, and despite his youth, Tim was found guilty and sentenced to six years in jail and a £4,200 fine. Money which, needless to say, neither he nor his family possessed.

He was immediately driven to a tough adult jail where, as a vulnerable young boy, we can only imagine in horror his likely fate.

A few months later, Jo who had stayed with her other children in Istanbul to be as close to Tim as possible, organised his escape. Wearing a wig and dressed as a girl he managed to reach the Syrian border before he was re-arrested and taken back to prison.

The outcry from the British press was so intense, the Turkish authorities transferred him to the Kalaba reformatory in the seaside resort of Izmir so he could serve his time alongside youngster of his own age.

There were scores of boys in the reformatory, some even younger than Tim and many serving long sentences for murder! I was told that, in rural Turkey, when one family fell out with another, it was a matter of honour for the son from one to kill the son from the other. So a lifelong vendetta was perpetrated.

I Get to Meet Tim

In 1972 I arranged, through Turkish contacts, to interview and photograph Tim for a Sunday newspaper.

After much paperwork and delays my ‘fixer’ and I were able to fly to Izmir and gain access to the prison. It was there my troubles really began.

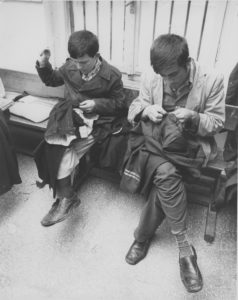

Having assured me I could photograph whatever I wanted, the authorities now decided that I could take only one picture of Tim and that he must be part of a group of other inmates.

Now a group photo, although better than nothing, was certainly not what I, wanted or was willing to accept.

My only alternative was to take what, in Fleet Street, we called ” a snatch shot”. In this the photograph is taken quickly and covertly. While Jo, Tim and some of the other Davey children were talking to the governor, I seized my chance and grabbed my shot.

Rather than raise the camera to my eye, which would have given the game away, I had fitted my Nikon F with a 20mm wide-angle lens. Using a small f-stop on this lens meant my picture was likely to be pin sharp without the need to focus. I and held the motorised camera at my side, and while they were chatting, pressed the shutter and hoped for the best.

The picture taken, I was preparing to depart when another warder, who had given every impression of disliking me from the start, intervened. He loudly and angrily complained I had taken an unauthorised, and therefore illegal, photograph.

My cameras were confiscated and I was led away to a small and grimy cell while they debated what to do. A few hours later, I was frogmarched back to the governor’s office. He demanded to know whether it was true that I had taken a picture without permission.

My Film is Destroyed

I admitted I had and with great reluctance finally said I would hand over my film for destruction. He agreed.

I ripped the 35mm film from the camera gave it to him with a smile and another apology. After several small cups of hot, sweet, black coffee we shook hands and I was allowed to leave.

End of story? Not quite!

Anticipating a likely problem, I had discreetly replaced the film containing Tim’s image with a blank roll. So the photograph was saved and a week later published in the Sunday paper as well as thirty UK and European magazines.

A few weeks later, Tim was pardoned by the Turkish government and returned home with his family. When I last heard he was working as a printer in Manchester and seems to have fully recovered from his ordeal.

In 1974, he and his mother wrote a book on their adventures, entitled Timothy Davey, it gives a detailed account of his experiences. Now out of print it is well worthwhile reading if you can find a second hand copy.