COVERING DEMONSTRATIONS

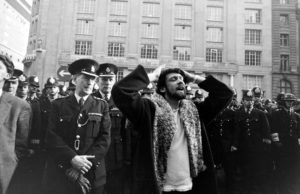

The ‘sixties were a time of youthful protests, against the Vietnam War, Nuclear weapons, capitalism and government secrecy, in the two cities where I regularly worked, London and Paris.

Do remember RSGs?

The acronym stood for Regional Seats of Government, top secret bunkers from which local government officials would operate after a nuclear war.

A woman friend of mine was arrested for “singing” an official secret and my friend, the mathematician and philosopher Bertrand Russell, then in his 70’s was arrested and jailed.

The protests and demonstrations became increasingly violent as years went on.

This was especially true in Paris, where the riot police took a no holds barred approach to riot control, with the immediate target of their assaults on photographers and journalists.

That way. they could get down to the serious business of beating up the protesters without any photographic or film evidence of their brutality.

When I first began to cover protests, at the start of the ‘sixties, they were largely good-natured affairs all sides. By the early 70s, photographers were having to take increasingly elaborate precautions for their own safety.

On these assignments I generally used my Nikon camera’s fitted with fairly wide lenses. My favourite was a 24mm, as I liked to get as close as possible to the action. But I would also have at least one camera fitted with a slightly longer lens, such as a 135mm, for close-ups.

An exception to my lens rule was, as I mentioned in a previous blog, was when working in Ireland. There I would sometimes use a 240mm or even a 400mm Novoflex lens. These allowed me to secure good shots from a safe distance under dangerous circumstances.

The trouble was that this lens, from a distance, very much resembled a grenade launcher! It had a rifle like trigger with which one could focus the lens by squeezing on a bar.

As such, you were quite likely to get shot at by any of the one or all of the three sets of combatants, the British Army, the IRA and the Provos. To reduce the danger, a least on press photographer painted the end of his Novoflex bright yellow to help all sides recognise it!

One of the hazards, when covering a fast moving demo, was running out of film.

In those days most photojournalists used cameras which would shoot a maximum of 36 pictures before you had to change rolls.

There were camera backs that enabled you to shoot up to 250 pictures, but these made the camera rather cumbersome and were expensive. I saw one or two in the course of my career, they seemed especially popular with sports photographers, but never used one myself.

As a result, photographers could not just “bang away” or they’d risk running out of film at the vital moment. Even in the most chaotic, hectic, and potentially hazardous situation it was necessary to frame each shot carefully and use film sparingly.

On a side note, I occasionally filmed for television and one of the cameras widely used on news stories, which did not require sound, was the 16mm Paillard Bolex which took 100 foot magazines. These were, typically, shot at 24 frames per second so they could be synchronised with sound back in the editing suite. This meant one had just four minutes of film in the camera.

When it ran out, the camera back had to be opened, the old roll removed, a new one inserted and carefully threaded through the ‘gate’. If any dirt, dust or small strips of emulsion between the film and the lens it produced a fault that could not easily, quickly and cheaply, corrected after processing. This was known as “hair in the gate” and you sometimes see it in amateur movies.

This may be hard to imagine for today’s photographers, using digital cameras able to capture hundreds of images without running out of memory. But I still think that framing a shot makes for better photography than ‘hose piping ‘ the camera over a scene in the hope of catching something worthwhile.

My photographs, below, show different marches and scenes of violence in London at the height of the demonstrations. The first picture includes a number of other press photographers covering the demo, all using 35mm cameras. On the steps up to the house, you can see two film crews covering the event. In those days cameramen – and they were mostly men – were, and often still are, accompanied by a sound engineer who held the microphone and operated the recording equipment.

He, and again it nearly always was a he, had to be attached to the camera by a cable. When covering a state visit to Denmark by a Soviet leader I remember one cameraman walking slowly backwards, while busy filming, the strolling delegates, accidentally falling into a castle moat and pulling his sound recordist in with him. Much to the amusement of the Soviets.

If you would like to know more about my photographic work or have any questions about the equipment used please contact me via the website below.

For more trips down memory lane go to www.thewayitwas.uk where you can also purchase a copy of my book The Way It Was – A Photographic Journey Through Sixties Britain. This contains a detailed description of the technical aspects of the photographs and how they were taken.

I also give occasion talks, at no charge, to photographic clubs and societies within easy distance of Brighton where I am based.

l