My Quarry Nightmare

One of the most entertaining, and alarming, contacts I made during my days as a photojournalist, was with a remarkable showman named Joe Weston- Webb.

In the late ‘sixties, Joe set up teams of drivers who performed astonishing, and astonishingly dangerous, stunts using cars, trucks, vans and motorbikes.

The first, named Destruction Squad, consisted of a group of young men prepared to take any risks for the sake of a good car stunt. The second, Motobirds, comprised a dozen young ladies who performed similarly hair-raising stunts on motorbikes. One of them, who later became Joe’s wife, also performed as a “Human Cannonball” and I will be featuring her amazing stunts in a future blog.

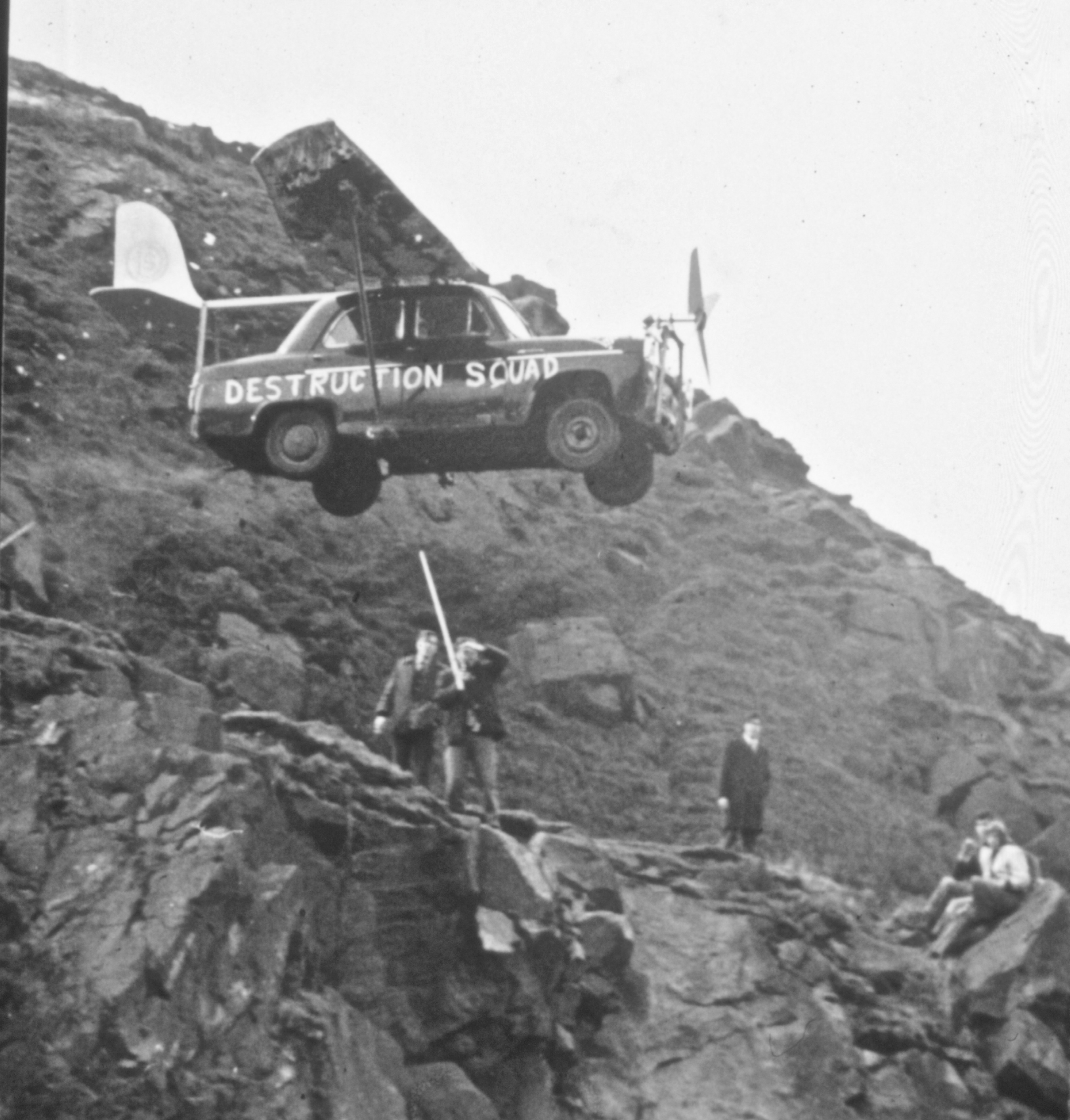

Joe’s Flying Car

One evening, Joe telephoned me with an idea for a car stunt. He would fit an old family saloon with wings, tail and a propeller, then attempt to fly it off the edge of a 100ft quarry.

Joe had two questions for me.

Would I like an exclusive on the photographs and did I think he should alert nearby Manchester airport?

My answers were a firm ‘yes’ the first and a ‘probably not’ to the second.

Very early one morning, in late November, I drove to the quarry where stunt was to take place. The day was grey and drizzly. Hardly ideal conditions for good photography.

My heart sank even further when I discovered the quarry consisted of very dark rocks made even blacker by the leaden sky. The car too was painted black, making it hard to distinguish against the background.

Nevertheless, we decided to proceed in the hope the weather conditions might improve.

Problems to be Solved

A rehearsal, in which the driver took the car to the edge of the drop but not over it, turned up an unexpected problem.

One of the six bolts, used to secure the wings to the roof, came within half an inch of the driver’s helmet. This, as he pointed out, posed a major hazard. When the car hit the water, the impact could well drive the bolt through his crash helmet and into his skull.

This problem was solved by lowering the driver’s seat a couple of inches so that he was virtually sitting on the car floor. This, however, produced another problem. Now he was too low to see the start of the jumping ramps which would launch the car into space. To miss those ramps meant almost certain death, since the car was likely to plunge vertically down the rock face rather than into deep water at the bottom of the quarry.

The whole assignment was rapidly turning into a nightmare with lousy weather and endless technical hold ups.

After much head scratching, Joe’s mechanics came up with an answer. Two long, thin, pieces of wood were attached to the end of each jumping ramp. All the driver had to do was aim for the strips and he would hit the ramps.

I Call Off the Stunt

By 3 o’clock in the afternoon my hopes that the weather would improve had been dashed and, to add to my problems, being late in the year it was rapidly getting dark.

Reluctantly I had to insist that we postpone to the following day. Even more reluctantly Joe agreed.

Twenty-four people were involved in the stunt. These included, apart from myself, Joe and the driver, motor engineers, ambulancemen, and six professional divers. These men and women were tasked with saving the driver if he became trapped in the wreckage at the bottom of the 30ft deep quarry. Inside the vehicle, strapped to the floor where the passenger’s seat had been, was an air bottle and a demand valve which would allow the driver to breathe while the divers set about their rescue work.

Joe urged all involved not to say anything about the stunt, especially if they were out drinking that night. It was, he stressed, essential to maintain the secrecy in order to protect my scoop.

News Leaks Out

The following morning, it became apparent that news of the stunt had got out. The road beside the quarry was lined with local and National photographers. While the quarry itself was on private ground, and Joe’s security men were able to exclude any photographers from the immediate location, there was no way any of us could prevent them taking photographs from a public highway.

Although any photographs they got would not be especially good, they would have made my shots almost worthless.

I pointed this out Joe who said he had an idea. This turned out to recruit twenty burly young men from a local fairground to whom he handed blankets.

The Car Finally Flies

Although the weather was still far from ideal, I decided that we had to go ahead. After taking numerous pictures the car and the driver at the quarry’s edge, I descended to a small ledge, just above the water, and prepared for action.

A few moments later, the saloon came flying through the air just beyond the end of the jumping ramps. As it did so, the fairground lads all jumped into the air together, each holding one end of a blanket. This effectively blocked every other camera on the road.

Apart from myself, the only photographer to get any shots was a TV cameraman – you can see him standing beside stunt organiser Joe Weston-Webb, with one of the thin wooden lathes used to guide the driver onto the jumping ramps flying through the air nearby.

The car hit the water with a sound like a bomb exploding and almost immediately disappeared from view. An anxious forty-five minutes followed before the driver emerged for the black waters, surrounded by his rescuing divers. He was unscathed by his experience and could claim the record as the only bad to ever fly a saloon car off a quarry.

A Successful Shoot

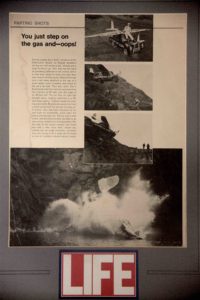

My pictures made a double page spread in the British National newspaper and a whole page in Life magazine which had commissioned them.

It had been a nightmare assignment, but one which worked out perfectly for me in the end. As I will reveal in an upcoming blog, this is not certainly something that can be said about all of Joe’s stunts that I covered during the ‘sixties,