The Way It Was With Colour Photography

Ever since the first black-and-white photographs appeared, in 1839, photographers dreamed of being able to take pictures in colour.

This became a reality, in 1904, when two French brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière introduced their Autochrome system. Three years later their factory, at Lyon, started to produce Autochrome plates commercially.

Critics and public alike were captivated. Alfred Stieglitz, wrote enthusiastically: ‘The possibilities of the new process seem to be unlimited… soon the world will be colour-mad, and Lumière will be responsible.’

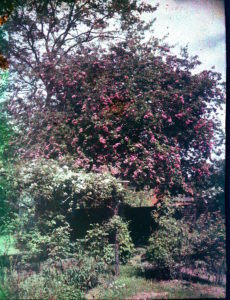

A glass, quarter-plate, Autochrome photograph circa 1908

So were Autochrome plates that, by 1913, 6,000 were being manufactured every day.

How the Plates Were Made

Starch grains, from potatoes, were pulverised and sieved to produce individual starch grains, between 10–15 microns in diameter. These were dyed red, green and blue-violet, mixed and distributed evenly over glass plates, then varnished.

The next step was to fill gaps between the grains, using charcoal powder, and compress the plates, under five tons of pressure, to flatten the grains.

In the final stage, the plate was coated with a light sensitive, panchromatic, emulsion.

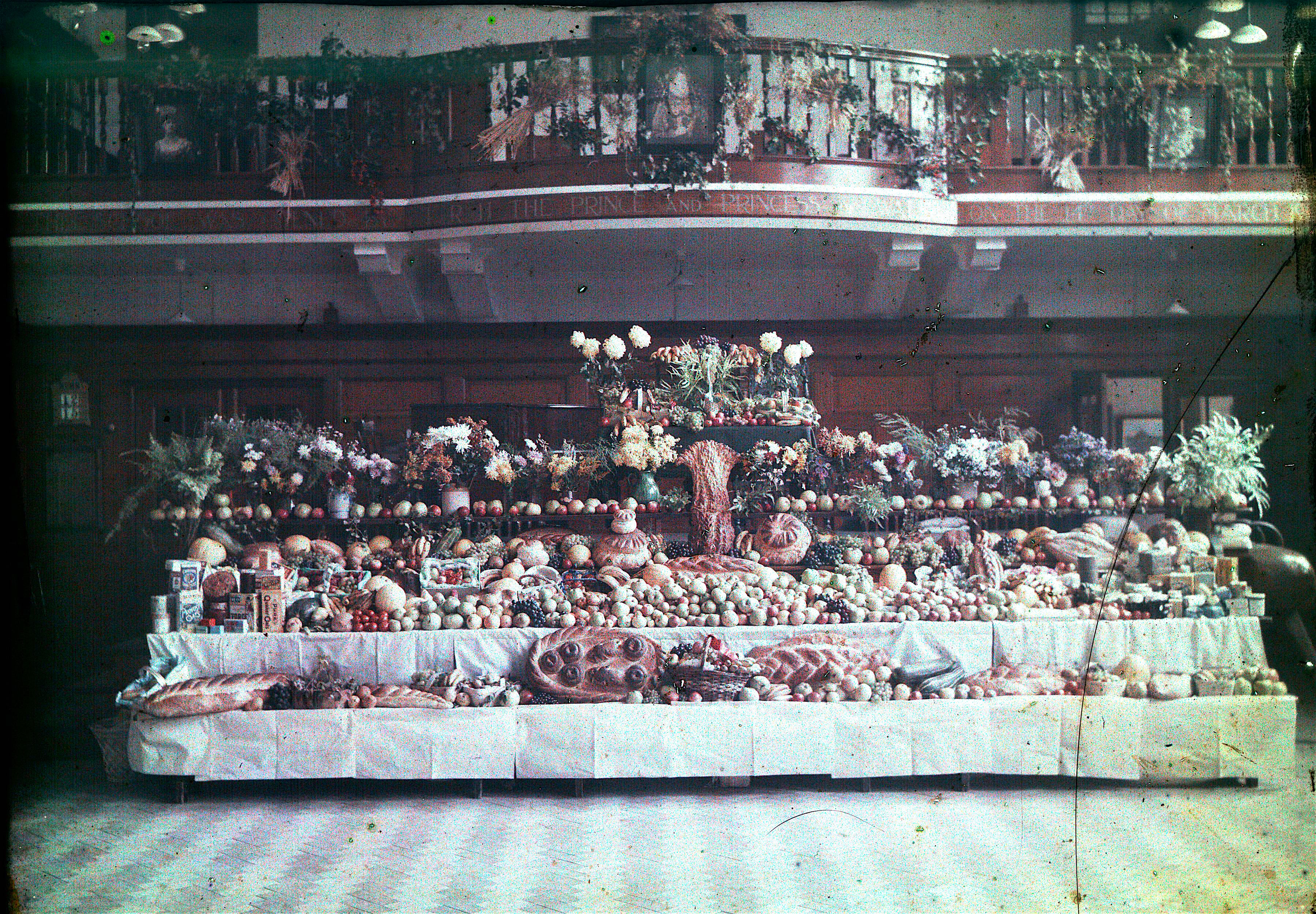

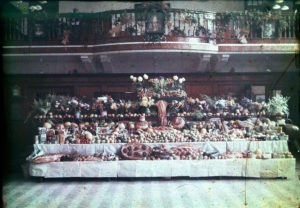

Fruit and Flower Show produce on display in a Village Hall, circa 1911. From a half-plate glass image

How the Process Worked

The great advantage of Autochrome plates, over earlier colour processes, was that photographers could use their own cameras. No specialised equipment or knowledge was required.

The drawback were the long exposure times.

Even in bright sunshine, Autochrome plates would last 10 seconds or longer while in a studio, no matter how powerful the lights, exposures of 30 seconds or more were typical.

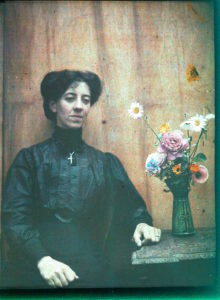

French woman photographed in 1909. Note the careful pose to avoid movement during the long exposure time required for the Autochrome system. From a quarter-plate glass image.

After exposing their plates, the photographer reversed process them to create a positive image.

When viewed, by transmitted light, the millions of minute red, green and blue- violet starch grains combined to accurately reproduce the original colours.

Although individual starch grains cannot be seen by the naked eye, groups of them are visible, giving these photographs a distinctive and subtle beauty.