The Day a Flying Tiger Almost Killed Me

During my career as a photojournalist, I firmly believed an aircraft would kill me.

On an overcast September day, in 1968, one almost did.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s not that I have a fear of flying. I’m convinced the most dangerous part of any flight is the journey to and from the airport.

But my job meant I flew on a large number of aircraft, from the RAFs mighty Hercules transport planes to single engine tiddlers in Asia and Africa. Flying machines and pilots which, at least in the ‘sixties, often constituted a major risk to life and limb.

The Hungover Pilot

Take, for example, an early morning flight I made on a tiny local airline in North Africa in 1962.

The previous night I had overindulged with friends and, the following day, felt fairly wretched as I sat in a tiny departure lounge waiting while the aircraft was fuelled.

Sipping a coffee on the seat opposite me, and looking as wrecked as I felt, was a young man holding his head in his hands and groaning softly.

“Tough night?” I enquired. He nodded miserably. “Me too,” I commiserated. “I really don’t feel much like flying this morning.”

“Neither do I,” he agreed miserably. “Trouble is, I don’t have any choice.’

“You’ve got to get somewhere in a hurry?” I suggested. He shook his head.

“I’m your pilot!” he told me.

‘Hare and Hounds’ with a Bi-Plane

Anyhow, to get back to that dull September day.

A few weeks earlier in El Vino’s, a famous Fleet Street watering hole, I got talking with man named Brian Lecomber who, I seem to recall, worked as a sub-editor on a motoring magazine.

After a while, our conversation turned from cars to aircraft and he told me he belonged to a Tiger Moth club based just outside London. Brian went on to recount how, with his friends Tony Cheshire and Mark Grandis, he liked to play a dangerous game of Tiger Moth ‘hare and hounds.’

Tigers at Play in 1966

‘Bombing’ the Hare

What they did was this.

Pilot Tony, flew the bi-plane while Brian stood on the wing and Mark, wearing a padded jacket, ran across fields trying to dodge dummy bombs, fitted with smoke grenades, Brian attempted to drop on him.

I could immediately see the photographic possibilities and asked whether they might be interested in my covering their highly dangerous stunt.

A few days later he got back to me and said they would be delighted to help me get my shots.

How the Pictures Were Taken

After surveying the ground over which the ‘chase’ would take place, I decided to cover the story using two cameras.

I would operate one while the second would be fitted to the tail of the Tiger Moth and controlled by pilot Tony using a microswitch taped to his joystick and connect the camera by a long cable.

I attach one of my cameras to the Tiger’s Tail

To get a very low angle shot of the aircraft, I would lie on the ground while the ‘hare’ would sprint towards me closely pursued by the bi-plane.

The Stunt Starts

When the day came, I attach the motorised Nikon F to a special board we had constructed that spread the weight over the aircraft’s canvas covered tail plane. The cable attaching it to the pilot’s microswitch was run along the side of the aircraft and into his open cockpit.

I lay flat on the grassy field and prepared for action. Tony Cheshire, was one of the U.K.’s most experienced Tiger Moth pilots, so I was confident he could pull off this extremely dangerous stunt.

The Stunt Goes Wrong

The Tiger took off, and circled at low altitude while Brian clambered from the front cockpit and, armed with several dummy bombs, made his way gingerly onto the wing,

Mark began running towards me across the field, while the aircraft dived to within just a few feet of the ground.

The first attempt was quite successful with Brian’s ‘bomb’ landing just a few feet from the target and exploding in a cloud of smoke.

Always eager for more, I asked Tony to make one further sortie.

Over the walkie-talkie I heard him cursing.

“This thing flies like a brick factory with a man on the wing,” he protested. But he agreed to make one more run.

The bi-plane swooped in, only feet from the ground, and just as it passed over my body, hit an air pocket and dropped even further.

One landing wheel struck my back, just behind my neck, and carried on along my spine before Tony was able to recover and climb quickly to a safer altitude.

At first the pain was so extreme, that for a few moments I feared my spine had been crushed. After a while things settled down a bit, and my assistant was able to drive me to the nearest hospital.

An x-ray confirmed that my injuries amounted to no more than severe bruising and I was discharged with some painkillers. For some days afterwards, however, I was able to make out the impression of the aircraft’s tyre on my back.

A Sad End to the Story

My pictures came out well and made publications around the world. Sadly, most of the negatives were subsequently lost when my agent moved offices.

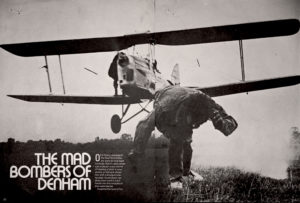

Below you can see the one photograph that survived, taken by pilot Tony using the switch on his joystick. The cable connecting it to the camera can be seen running along the side of the fuselage.

The shot I took from the pit only exists in one of the magazines which published it and these too are pictured below.

This assignment illustrates how interesting pictures can be obtained by remotely fired cameras, providing they are set up correctly and the picture appropriately framed.

These days with lightweight, high quality, cameras like the GoPro amazing photographs can be taken without the photographer being anywhere near the scene. But in the 60’s, radio control cameras were few and far between. The ones I used had been especially made for me.

Tech Details

The tail mounted Nikon used Kodak Tri-X film, rated at 400 ASA, with a shutter speed of 1/500th second. Its 20 mm wide angle lens was set at f8

My second Nikon had the same film and SA rating. It was fitted with a 35mm standard lens adjusted to f5 .6 with the shutter speed of 1/1000th second.