When an Underwater Stunt Went Wrong

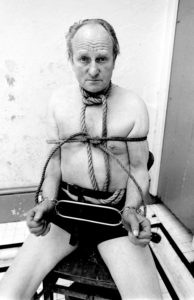

In the late 60s, I travelled down to a swimming pool outside Brighton, on the South Coast of England, to photograph escapologist, the ‘Great Omanii’, perform a hazardous underwater stunt. One, which the 65-year-old claimed, was ‘so dangerous, even Houdini would never attempt it.’

This involved the ‘Great Omanii’, better known to family and friends as Ron Cunningham, escaping from a weighted chair, to which he had been bound, strapped, chained and shackled, while 12 feet underwater.

To cover this, I used a Nikonos underwater camera fitted with a special lens housing designed, especially for me, by top American SCUBA diver Flip Schulke.

You can see this dome-shaped device on the camera I’m holding in the photograph below. This was taken during a dive not in a drab swimming pool but the rather more glamorous surroundings of the Indian Ocean.

The housing enabled me to use a 21 mm lens, normally used on surface cameras, below the waves. Even though the water in the pool was clear, and the visibility considerably better than I could expect on most dives, it was still better for my shots for me to be use a super wide-angle lens and get as close to the action as possible.

I was using my favourite film stock, Kodak Tri-X film, which I had rated at 800 ASA, twice the normal speed, to enable me to shoot at 1/250th at f3.5

The Stunt Goes Wrong

As Omanii, was tied and shackled by his helpers, I took photographs using one of my surface Nikon cameras fitted with a 35mm lens.

When all was ready, I hastily pulled on my air cylinders and dived into the pool to catch the moment when he was lowered into place.

Omanii had told he that he had to get free within two minutes or risk death by drowning. Once the ropes, which had been used to lower the chair into the pool were removed, there was no other way of his getting out.

At first the stunt seemed to be going according to plan.

In less than ninety seconds, Ron had freed himself from the wrist shackles, removed the padlocked belt securing him to the chair and freed one of the main ropes.

Then he started to struggle.

A second rope would not budge and, while it remained in place, he could not free himself and seemed about to drown.

Unsure whether this was just part of the act, designed to make it look even more difficult than it actually was, I continued shooting. But when the two-minutes mark was passed I realised that something had gone seriously wrong.

The Photographer’s Dilemma

This confronted me with a dilemma that has faced many photojournalists over the years.

Should I put down my camera and go to his aid, or continue to take pictures in the hope he would manage to break free on his own?

My opinion, hard though this may seem, has always been that my job as a photojournalist was to record what happened rather than try to intervene.

This proved especially hard in war zones or when covering riots and violent demonstrations, where people are being hurt, or even killed. But I have always believed that, a journalist should remain detached, as far as possible, from the events unfolding around them.

You may have seen film footage of the evacuation of British troops from the beaches of Dunkirk in 1940. What may have struck you a slightly odd was that there is so little footage of this historic moment.

According to one report, I read, this was due to the fact that the one film cameraman on a ship conducting the famous rescue, filmed for only a few minutes before abandoning his camera and going to help pull the exhausted troops aboard.

Was he right to do so?

In my view, although his actions were perfectly understandable, at a human level, it would have been better had he stuck to his ‘day job’ and recorded the events in as much detail as possible for posterity.

What do you think?

Teenager to the Rescue

Just as these thoughts raced through my mind, I suddenly saw a slim figure dive into the pool to help.

Michael Carew, the ‘Great Omanii’s’, 13-year-old grandson, had spotted his grandfather in danger and plunged to the rescue.

After an agonising struggle, he managed to cut through the rope and assist, a by now exhausted, Ron to the surface.

Back on the poolside, Ron embraced his thoroughly soaked grandson and told me: “I assured Mickey I’d be free in just over a minute but one of the ropes expanded and wouldn’t budge. He almost certainly saved my life.”

I had expected the story to turn out modestly well, but the lad’s dramatic dive to the rescue meant my pictures were published in over 400 magazines and newspapers around the world.

End